The Communicator (Part 1)

Metanoia - Chapter 2- Life Path 3

Character Chart: A Map to the Nine Lives

“Just like our eyes, our hearts have a way of adjusting to the dark”

-Adam Stanley

A little girl walks through the village streets in the company of her mother.

Through the eyes of the mother is a love, and an undying sense of duty attached to it. She guides her child, comforting her by stroking the small tuft of unusually colored feathers on the back of her neck while waiting at each intersection.

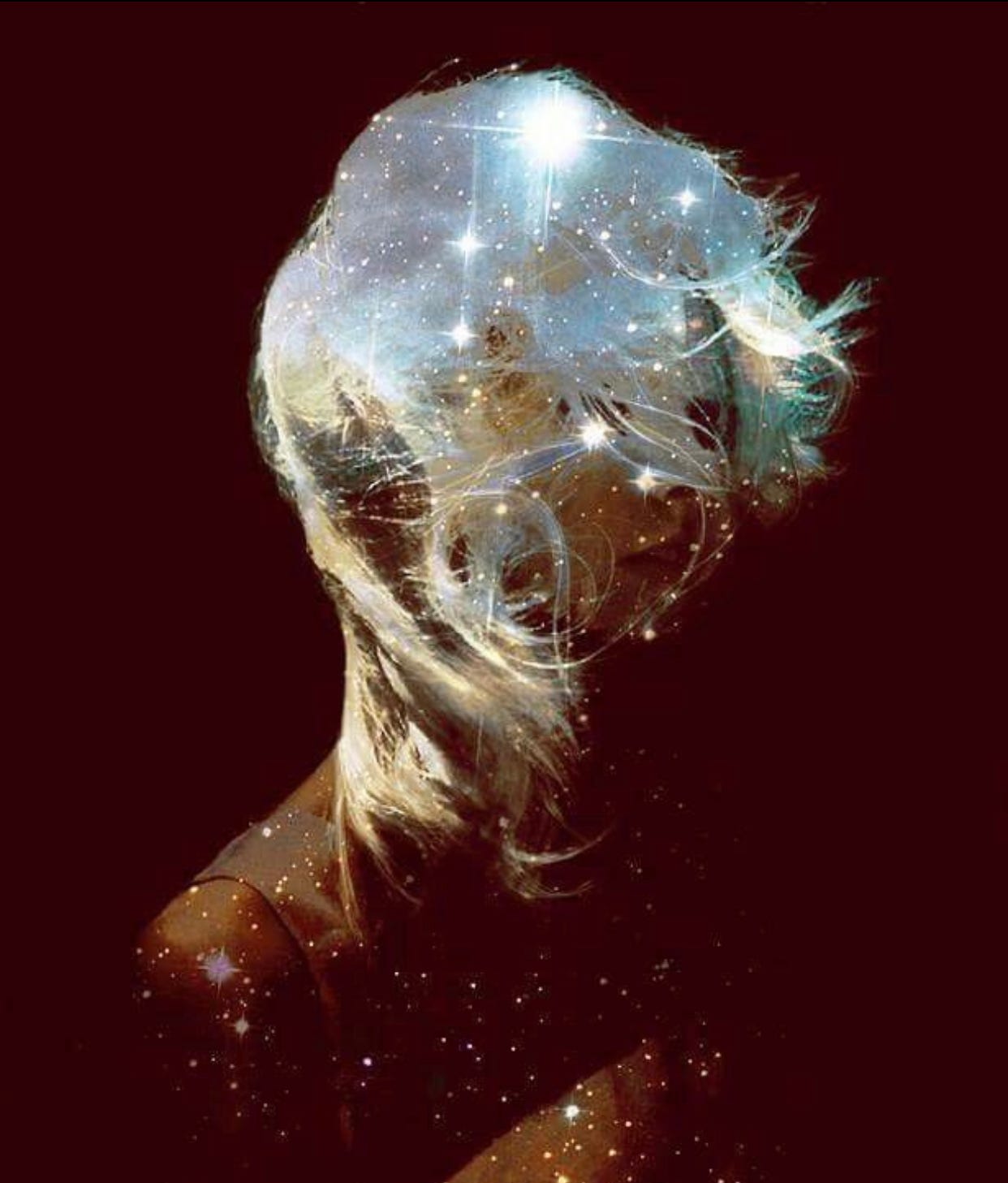

Through the eyes of the child is a sky bluer than blue, clouds with striking definitions and lines, and every surrounding surface, both fabricated and natural, fuming with color. In her view there is chaos with order, compassion with cruelty, and the confusing impenetrable unification despite it all.

“How does everyone learn all the letters of the alphabet? There are too many of them.” The girl protests. She was thinking about her language class and how they had just finished introducing all 72 letters. With only a vague understanding of them as a whole, she could not grasp the possibility of going from an empty understanding to complete fluency of the written word.

“It won’t be hard at all. You will see and hear it over and over again, until it becomes natural. You’ll see letters and words one day, and just know them automatically.” the mother reassures.

She felt overwhelmed by all the things she had to do to catch up to her older siblings. What she wanted most of all was to know how to read. How uncomfortable it was to be shy yet have an inescapable need to express. As the youngest of three in a busy family unit, one learns to keep to themselves, to stay out of the way, and to not draw unnecessary attention.

They pass housing communities, food centers, people on bikes, deliveries being made with domesticated animals. The child fusses with her hair, which won’t seem to part in the way she wants it to. When you’re a little girl, sometimes the only thing you have control over is the way you part your hair.

They are surrounded by a busy mob, adults passing mere inches away from the little one’s nose, acting as if the mother and her child were not a concern for collision. The low chatter of several voices, sounds of crates being stacked, and creaky wheels allocating resources throughout the village adds to the assault on the senses. Yet everyone has a set rhythm, a cadence vibrating at a specific tone. Effortlessly, it converged in harmony.

Every day, the world passes them by like this during the walk to school until they reach their destination, and the compassionate caretaker leaves her biologically eclectic little girl at the gates of the school gardens.

“Remember, you’re beautiful” she says.

Without control, a few tears escape the child’s strained eyes as she turns her head sternly towards the school. She knows she is not.

The little girl was me, born an anomaly within the system, something no one knew how to approach.

The walk to school was the only time I had with my mother in my early years. My father passed away before I knew him, leaving my mother Sonia having to put in more time in the work force in order to sustain the four of us. Her only option was to take the night shift at the local medical facility, because someone had to be home in the morning to take me to school, as Zenon and Remi started at an earlier time and left long before I did.

Other than these walks, I do not remember much of my early childhood. Perhaps I knew I would not want to remember. It was as if I went somewhere else after my mom dropped me off every morning.

Way back before my school days when I was barely more than a toddler, I witnessed a purple bird drown in a public fountain. Something suddenly came over me as I watched it in peril. The wall was too tall and too steep for it to climb over, and the water falling down from every direction kept dragging her under. First fear, followed by fighting, struggle, abandonment of hope, defeat, then vacancy. I saw it happen from a distance and could not articulate my panic as Zenon and Remi restrained me from running into the water. When I got older, I began to relive this memory in my sleep. Every time there is nothing I can do for the bird. Every time I become too familiar with what death looks like. The fear was real. My fear of death was relentless and never changed. My heart could not handle the stark difference between life and its absence. I was born with deformity and sensitivity, which was like being too much and not enough, and afraid to live, because living meant dying.

But I remember having someone, or something rather. He came to me when I was by myself so that I wasn’t alone when I was alone. I called my imaginary friend Bei, which was the name of a heroic character in a story my mother used to read to me, and what I forced my siblings to read to me. I’m not sure why I decided he was male as he had many feminine features that I can recall. Admittedly, I’m not certain why I was seeing people who weren’t there either, so it wasn’t a question I’d dwell on.

Bei kept me company and I forgot my feelings when he was there. He never said much, just held my hand when I moved where I was playing, sit and watch. The memories were brighter too, as if the sun was stronger. A golden hue followed him.

I also had Fren. Our parents were friends with one another before we were born, and both being caretakers, had found each other in the nursing field. Fren was an Artisan, and so was I, technically. That is the track my mother suggested I go on, since my brother Zenon was already a caretaker, and my sister, Remi, already a Technician. It would give more balance to the family, and a possible life long companionship with Fren. My mother saved my life with this decision, as she knew it would. All you need is one friend, just one solid friendship, and life is instantly bearable no matter what condition.

When school first began, we played a game in gym class called Mission Synergy. It’s the first real challenge experienced by the Umari, having it introduced in an untimely manner by the administration on purpose.

We gathered our tiny selves along one wall of the gymnasium, a clear red line displayed before us defining the beginning, and the obstacle. The beginning was a very small safe zone between this red tape and the wall. Our objective was to make it past this red tape, over the expanse of the gymnasium, and into the safe zone on the other side without touching the bare ground. If you touched the ground, you were forced to start over. The game was won when everyone made it to the other side.

A giant blue mat was placed in the middle of the room, taunting us, serving as the first vital checkpoint, and what we all had to think about before even considering making it to the other side. In addition to having this blue mat, some of us were equipped with scooters, some with circular stepping pads, or nothing at all. Ropes and things were strewn across the forbidden barren areas that were difficult to reach. The game is won when every single one of us makes it to the other side. We were to learn the foundation of our people, and to become aware of our own role in society, whether it be of an Artisan, Technician, Laborer, Protector, Entrepreneur, or Caretaker, and work together as a unit. They told us this in a way we could understand before the session, and left us to the task.

I was the only child who didn’t know how to begin that day. I could tell from the looks on the children’s faces what the adult’s reaction hid at the sight of my physical appearance. No one knew what to think of me. I remember looking down at my rounded finger tips that were supposed to be that of an Technician. My hair was long and dark brown like any typical caretaker, and my eyes a little wider and more alert for an Artisan. The small patch of feathers behind my neck were the three colors of these tracks: yellow, indigo, blue; Caretaker, Artisan, Technician.

My first attempts at this challenge were awfully confusing. It appeared that before I was matriculated into the one track system of our education, my behaviors were expressed in the same conglomerate manner that my body had assumed. I started leading from the front like the entrepreneurs who hastily wanted to make it to the other side, and then fell back with the protectors who were leading from behind. I proposed ideas and methods of success like the Technicians and Artisans and was mindful of those around me like a caretaker. It didn’t take long for me to realize that this was somehow disrupting the entire flow of the group. It was as if each child had a particular weight in their position, and I was disrupting the balance by not being all of one form at any given time.

It was the day that the chameleon was born. I discovered a method that not all children with my deformity were able to adopt. I found that although I couldn’t rely on my instincts, I could evaluate what role needed to be filled at in a given situation, and revert to that person completely. Surrounded by my peers, I could not be a caretaker, Artisan and Technician. I could only be one. Once I found an empty groove to fill, I simply assumed that position repeatedly without diverting from the assignment.

“FORM DICTATES FUNCTION!” We were in Science class and Professor Sanes is lecturing that day.

Fren discretely turned her face towards me as Sanes paused his rendition.

“There goes that old bird again. He starts every lecture with this.” she said to me quietly.

I stifled a laugh and smiled. It was true.

He continued…“Look at this beak!” He said while pointing to an ornamental bird mounted on a plaque of wood. “Its particular shape is fashioned for capturing yin beetles an inch below the soil. Think of the hooves of our livestock. When you examine these structures, you can see exactly where it belongs in its environment, and exactly what it is fit to do in this life.”

I’ve heard this all too many times before.

“In understanding this law of nature, we can begin to understand ourselves better. Our people have evolved in this way, although slightly different. Umarians have gone beyond the shape of their appendages, and further to the colors of our tufts. Perhaps it is our social structures that brought about this unique occurrence, although it is not certain. There is limited understanding of our ancestry, but the environment and its organisms around us have already provided quite an abundance of knowledge about our world.”

I wanted to ask why we wouldn’t probe further with our understandings, but already knew it wouldn’t lead anywhere.

Then came the part where Professor would become enamored by his own field and get “existential on us” as Fren would put it.

“The way every organism is so fine tuned, so perfected to fit within the specific niche of its own existence is remarkable. How interesting that a species such as the Umari would be able to capture the usefulness of being able to see its counterparts for what they are, and then work together as a unit more effectively as a result, work together in order to reap the benefits that only one Umari cannot attain individually.”

Sanes was talking about the current understanding of ourselves, that we evolved having a correlation between physical appearance and behaviors in order to be able to identify the purpose of ourselves and others to work together. Laborers have sturdier bodies and scattered minds. Their hands were a little wider and muscular. They had dark hair and the tuft of feathers on the back of their neck was brown. Artisans appeared more delicate, having larger eyes with neither light or dark hair. Their feathers were indigo, and had long fingers with pointed tips. Technicians also had long fingers, but their fingertips are rounded. They were the most focused of the personalities, having blue feathers. Entrepreneurs had light hair and alert expressions. They were light hearted, with orange feathers. Caretakers had light eyes and dark hair. They were exceptionally beautiful, and tend to have higher empathy with bright yellow tufts. Lastly, the Protectors had the darkest features, with black feathers and dark brown/ black hair. They were good at puzzles and had lean, fit bodies.

We discussed these differences in Theology class, the session that followed Science. There was a God associated with these parts of our society. A statue dedicated to each one was placed in the middle of school grounds, where Theology was held.

The Goddesses of Nurturing, Preservation, and Finesse represented our caretakers, Protectors and Artisans, while the Gods of Ingenuity, Specialization and Manifestation represented the Entrepreneurs, Technicians, and Laborers. The concept I appreciated most was how no position was more or less important than the other. They are all equally vital to our survival. This helped me come to terms with myself over the years. My biology was not helpful in the way it was for everyone else. It gave no clue to my place, and therefore no certain way to have a meaningful existence of contribution. But that didn’t mean I couldn’t be of service. Whatever I chose to do would still be important. It would just require a bit more effort, a bit more coercion on my part.

Our professor for Theology would harvest the fruit on the courtyard trees while we worked on our assignments. He had a long pole with a container at the top that had a strategically cut hole to capture each one and nick it off the branch. When enough were collected in the container, he would walk around to each of us and offer them. Professor Sliv was soft and kindhearted despite his slightly detached demeanor and restrained personality. I’m not sure anyone else noticed this about him, or if anyone even paid much attention to the idiosyncrasies of one another. I believe we were too focused on our linear positions to see the three dimensionality of one another. I could not succumb to the linearity even if I wanted to. I saw right through Professor Sliv. His biology was Technician and that was clear, but he also had a soft heart and a guarded personality.

It wasn’t until much later that I noticed something interesting about Umarians who decided to become teachers of the very young, before they began their specialized track and were taught by someone of their own biology and their own field. It was the most diversified, and the only diversified line of work for the Umarians. In our civilization, if you were born a Laborer, you brought things into physical manifestation. If you were a Technician, you were going to be doing specialized work that required concentration and methodical thought processes, such as a surgeon or creating plans for buildings. But there was a job that any Umarian could take, and it was teaching Umarians how to be Umarians. It was working in the school village, and teaching language, our belief system, and our knowledge of the world. It incorporated everything, and I found that these kinds of teachers were the most eccentric of the Umari, or at least the most eccentric a person could be while still walking a straight line. Professor Sliv served as an example of this to me.

Each day concluded with Language. For most, communication is a means to an end. It is simply a necessary function, and doesn’t go beyond that. If words were food, my peers dully consumed their meal out of routine and maintenance, while I relished each bite and dreamt up the possibilities of its use like a seasoned chef. Sound left our mouth and words were perceived through our vision, entering our psyche, placing thoughts and ideas that were not there otherwise. It was tool to understand the world, which I naturally craved, and a tool to understand my peers, if only my peers used it with greater depth. While I was grateful for Language class, I despised the way we were required to do assignments. There were formulas for everything, stories, essays, investigative papers, even personal letters. Why a formula was given for something that can produce infinite forms seemed nothing short of absurd. The alphabet is the most versatile component of our civilization. With it, nearly infinite combinations can convey infinite meanings, and these people were telling me how a story is supposed to go. It was all very peculiar and I did not understand. I decided at the young age of seven that would make a terrible teacher, having to profess these rules to children.

If your poll was still open I'd click the first option.

Perhaps that's because I'm understanding it in the way you intended it to be understood, I think. Plus of course there's the fascination of other worlds far away from this one. Other possibilities.

It's clear from this first part of the second life that she's one of those souls described previously who flits around without necessarily belonging anywhere in particular. It's easy to relate to that when you're in a place you know you don't belong...