It was a sunny afternoon in downtown Arcata when I found myself perusing Northtown Books on a trip to Humboldt County that I made for a job interview. It wasn’t my first time there, and like many places in California, I found refuge in this misty coastal town that embraced nonconformist souls unable to assimilate into the sickness.

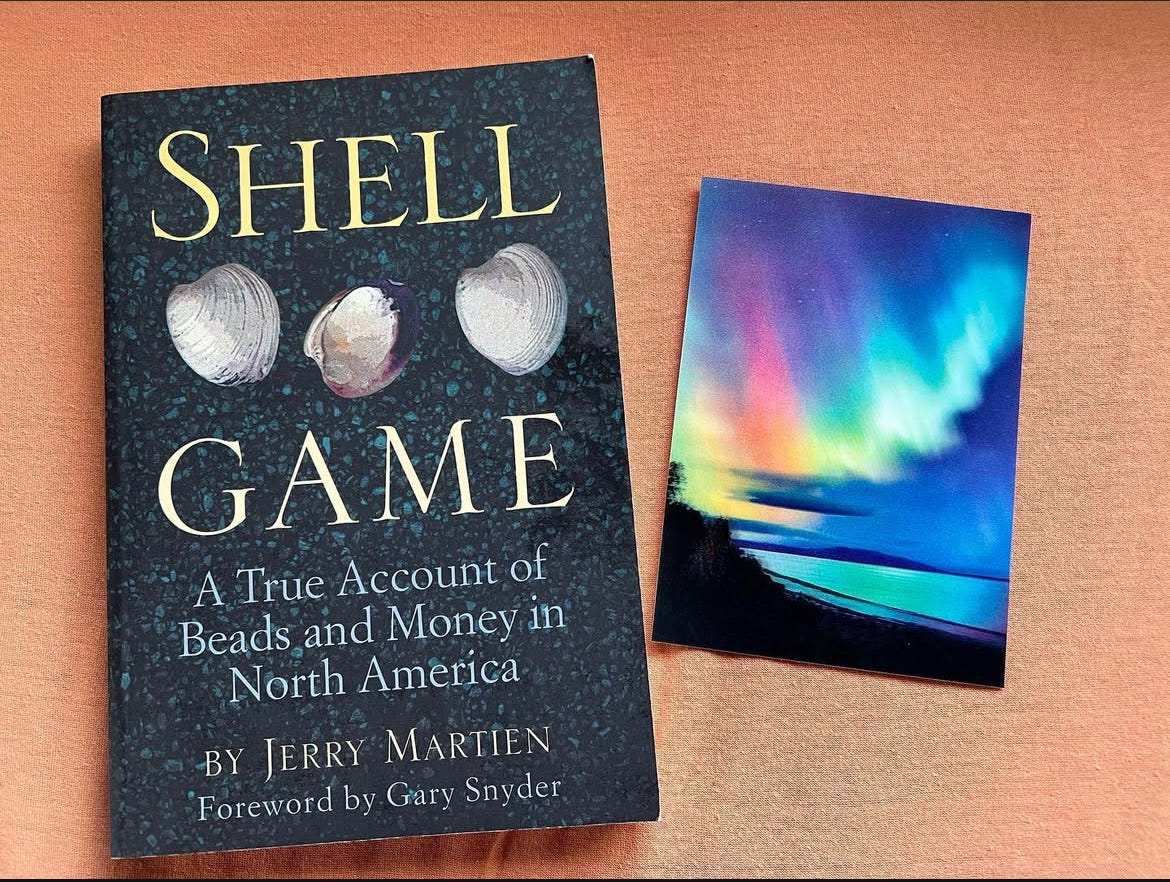

To my delight, I stumbled upon this book, which spoke of the beloved shells I knew so well having grown up on the Atlantic. The only part of history I ever genuinely enjoyed was the brief overview I got in third grade detailing the tribes and cultures of Indigenous America. Everything after that was endless iterations of what white people did, where, and how great our slave-owning founding fathers were. I was just a kid and so I couldn’t articulate the source of my unease, which later I was able to identify as the feeling that the history I was being told wasn’t accurate, or at the very least whitewashed.

I spent my formative years on the barrier islands of NY wandering around roadless beaches, learning what it meant to be connected to the spirit of place and exploring the magic of worlds within worlds. When I learned about the natives, I imagined what it was like for them to live there as I dug for clams, painted shells, and made jewelry. This was my source, and was/is the only thing that made sense to me.

We were told that wampum was a form of currency for some time, which fascinated me but was also something we knew nothing about. Needless to say, when I found a book exploring the nature of this exchange, I left with it feeling lucky I had stumbled upon a small piece of home, and eager to know more about the untold story.

Shell Game is a historical investigation of the nature of money and human exchange. Here, Martien depicts the appropriation of North America juxtaposed with his own pilgrimage around the country. The 1627 transaction in which Europeans “purchased” Manhattan with wampum (shell beads) reflected a profound cultural misunderstanding: settlers equated the beads with currency and property ownership, while Indigenous peoples saw them as part of a gift relationship, a binding contract, a symbol of alliance or sympathy, and a link to complex social and spiritual systems. In other words, the spiritual and moral bankruptcy of money that we still have today was used as a weapon against the Indigenous—and given all of what the gift relationship represented, against life itself (Gee, doesn’t that sound familiar?).

This book should be a required reading for all economic courses. Many are not going to like this reference, but the only way I can describe my understanding (or lack thereof) of money is by referencing the Disney movie Pocahontas. It’s the scene where John Smith is trying to explain gold to her. It goes something like this:

Smith: You know, it’s yellow, comes out of the ground and is really valuable.

Pocahontas: Oh! Here, we have lots of that *whips out some corn*.

Smith: No. This is gold. *shows her a piece of metal that you can’t eat and has imaginary value not based on existential needs or spirituality*.

Pocahontas: … lol what?

And at some point she breaks out into song about how dumb Smith is lol.

So you mean to tell me that this substance that I can’t eat, wear, or make shelter out of is what has value? This thing that bears no ties to existential reality or spiritual significance? If you can make that up, sounds like you can make up everything else around it too, like how much it’s worth in the imaginary marketplace and who gets the better deal.

Traditionally, schools (especially in U.S. history or economics courses) teach the origin of money through a linear, simplified narrative. It goes something like this:

We all *supposedly* began with direct barter (trading goods like grain for tools) →Money emerged as a neutral medium of exchange to solve barter’s “double coincidence of wants” problem. → This money is *portrayed* as evolving naturally from commodity items (gold, silver) to coins, to paper, to bank credit.

According to wall street wannabes, all of this was completely neutral and inevitable. I find that extremely hard to believe. Finance bros see it as some divine technological improvement—morally neutral and universally beneficial. Rarely is there discussion of how power dynamics, colonialism, or cultural erasure shaped monetary systems.

Non-European systems of value (like wampum) are often treated as primitive or pre-money curiosities, not as complex, intentional economies.

Some Key Takeaways From Shell Game:

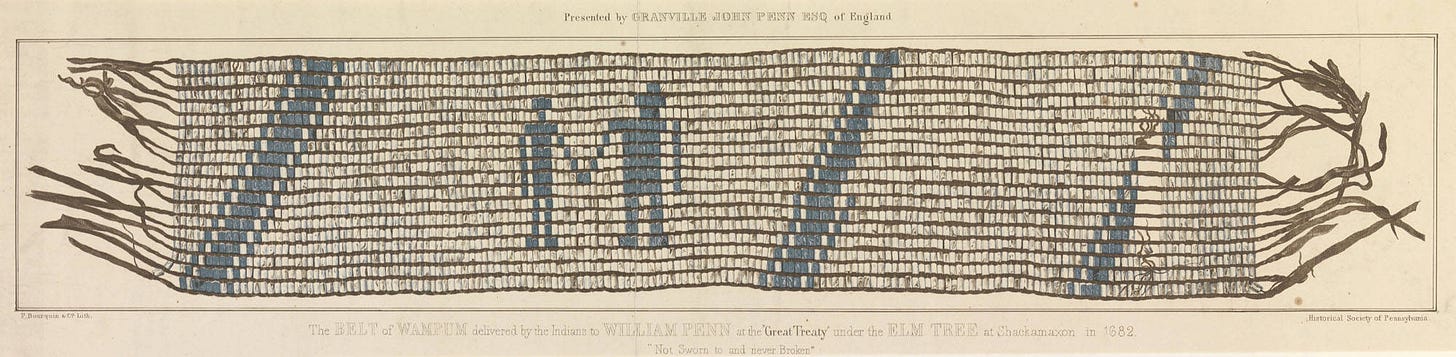

The pricelessness of wampum.

Wampum comes from quahog and whelk shells. They were painstakingly drilled, smoothed, and strung. Making even a single bead could take hours in pre-metal-tool times. Early makers used stone-tipped drills or reed drills with sand and water as an abrasive. The hole had to be perfectly straight otherwise it would crack the bead. White beads often symbolized peace or purity while purple beads represented solemn matters like mourning or serious agreements. The labor is what made this so valuable to Indigenous cultures, and it was used as a gift in peace negotiations, treaty-making, formal apologies, memorials, etc.

The desecration of what’s sacred.

Colonizers defiled all this by stripping wampum of its ceremonial and relational meaning, mass-producing it with metal tools, and using it as a crude currency to buy goods, land, and even people. What had been a sacred pledge of peace, alliance, and mutual obligation was recast as a commodity—its patterns reduced to decoration, its spirit emptied—so that it served the settlers’ system of profit, ownership, and domination instead of the Indigenous ethic of reciprocity.

Nothing has changed.

The process of inflation and devaluation that happened then is still going on in a wash-rinse-repeat cycle that never ends. Today, we watch the same story unfold on a global scale, as endless printing of money severs value from human and ecological life, leaving behind only a hollow shell of worth that fuels inequality and erodes the fabric of community.

Some favorite quotes of mine:

“Because money is a comparatively recent invention, and because it merged with or overlaid an older system of exchange, its nature and history are almost invisible to us, found if at all in the darkness of archetypal memory and the obfuscations of money managers.”

“Although money has disastrously failed us on countless occasions, we suppose theres no choice but to give it our faith and, as willing victims of mass delusion, endow it with a greater reality than the wealth was supposed to represent”

“Using money unconsciously—so as to cheapen the meaning of beads, for example, while making them too expensive for Indians to buy—is as deadly an act of spiritual greed as stealing people’s ancestors.”

“The fate of its artists is the fate of a culture. A country that does not pay its debts will eventually have no art, and then no topsoil, and no money. All the forms of wealth, spiritual and material, natural or manufactured, are essentially one. Its source is the gift of the Earth itself, again both of spirit and coin. Where the money does not honor that gift, the blues musicians are the first to go.”

The bottom line is that wampum was a gift—a sacred exchange turned into a commodity. Money, then and now, is drained of value and of spirit, where all that remains is a means of subjugation.

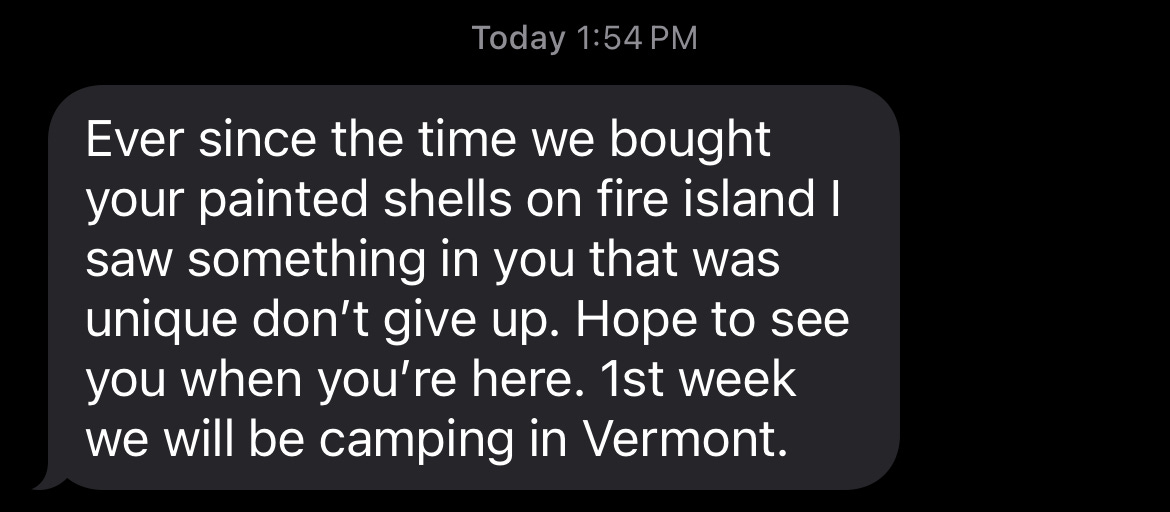

Despite my love and appreciation for the teachings of Indigenous cultures around the world, I’ve been hesitant to celebrate them with the fear of misusing them as a white-skinned woman born on stolen land. Do I wear these pair of earrings? Is it okay that I have a hand-drawn portrait of a South American man on my bookshelf? Should I even have these pieces of wampum that I found on Fire Island? Or, is it all cultural appropriation?

Sometimes I feel that we’ve made a mistake in framing this as a war between light and dark skin. The truth of the matter is, we were all Indigenous people at some point in our ancestral line before this disease took over. Somewhere deep in my Irish, Scottish, and Ukrainian ancestry, I was worshipping the sun, the moon, the stars, and the seasons. I was running around a forest somewhere with flute and drums, braided hair, matriarch underpinnings and a reverence for the Mother. Christmas, Easter, Halloween—all stolen and watered down to fit Christianity and other cultures. Our past has been diluted, forgotten, just like the native tribes of America, but because we look like our oppressors, our tribal nature causes us to assume their disfigured role accordingly. At the center of this charcoal heart, it has always been a class war, a crusade between soulless creatures and the rest of us.

I learned everything I know from the ocean. The natural world was and always will be the only thing that’s real to me.

This post is brought to you by Ed, a founding member of Metanoia, and someone who has always understood “the gift”.

Thank you Ed ❤️

Yes indeed thank you very much Ed! This was not only a profound education on aspects of indigenous culture I knew nothing about, but also very beautifully expressed. An unexpected gem of a read! 🙏

If interested I have expressed my own thoughts from my journals on the corruptive influence of modern currency concepts on our psyche in a recent post that can be found here: https://substack.com/@amanonerth/p-170102423

Big 😍 & 🐻 hugs!

Great post Kerry, thank you. History and refection are always so important. A very important book about a very important concept. For the best current description of what reciprocity and the gift economy actually look like, presented as a model we can all follow, please read the book "The Serviceberry" by Robin Wall Kimmerer, and add it to this post. Her "Braiding Sweetgrass" is a lengthier backgrounder on thriving modern Indigenous culture, and her "Gathering Moss" is perhaps my favourite book. I think you might really like Gathering Moss personally. It saved my life. Blessed be, and have a great day.